Geometry and the Density of the Universe

In Einstein's General Theory of Relativity, formulated in 1915, gravity is understood in terms of geometry rather than as just another ordinary force. Matter tells spacetime how to curve and the resulting spacetime curvature tells bodies how to move. For the special case of an expanding Universe, idealized as filled with a uniform density of matter, a good approximation on large scales, General Relativity establishes an intimate connection between the density of the Universe in comparison with the critical density and its geometry. A Universe of critical density (at constant cosmic time) has the familiar Euclidean geometry so well known to us from every experience and from classical perspective as taught in art class. However, a Universe of subcritical or supercritical density has a non-Euclidean geometry - hyperbolic if the density is subcritical, or spherical if the density is supercritical.

On small scales these different geometries are much alike. An ant on the surface of an apple might view its immediate surrounding as quite flat and might experience difficulty in figuring out that the apple is round. Likewise, if the curvature of the Universe would become apparent only on scales beyond several billion light years we might be deceived into believing that its geometry is Euclidean. Only on large scales - larger than the so-called curvature scale - do the differences between the geometries become large effects.

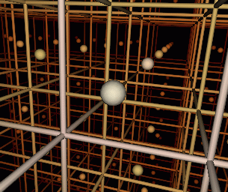

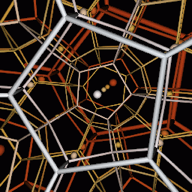

The following three plates illustrate the difference in perspective between the three possible geometries: a hyperbolic geometry, a Euclidean geometry, and a spherical geometry. In all three cases, space is divided into identical cells, whose edges are indicated by the rods. The balls within the cells are of identical size, and increasing distance is indicated by reddening.

Euclidean geometry

In the Euclidean geometry space is divided into cubes and one experiences the ordinary, familiar perspective: the apparent angular size of objects is proportional to the inverse of their distance.

Hyperbolic space shown here is tiled with regular dodecahedra. In Euclidean space such a regular tiling is impossible. The size of the cells is of the same order as the curvature scale. Although perspective for nearby objects in hyperbolic space is very nearly identical to Euclidean space, the apparent angular size of distant objects falls off much more rapidly, in fact exponentially, as can be seen in the figure.

Spherical geometry

The spherical space shown here is tiled with regular dodecahedra. The geometry of spherical space resembles the surface of the earth except here a three-dimensional rather than two-dimensional sphere is being considered. Perspective in spherical space is peculiar. Increasingly distant objects first become smaller (as in Euclidean space), reach a minimum size, and finally become larger with increasing distance. This behaviour is due to the focusing nature of the spherical geometry.

[The three above figures were prepared by Stuart Levy of the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign and by Tamara Munzer of Stanford University for Scientific American. Copyrighted and used with permission.]

What is the Geometry of Our Universe?

During the 1980s observations remained sufficiently crude so that a Universe of critical density was quite plausible. But more recent observations have made it increasingly difficult to reconcile a critical Universe with the observations.

It is known that, in addition to the luminous matter seen in the form of stars, the Universe contains a large amount of "dark" matter, in particular in the halos around galaxies. The presence of this dark matter is inferred from its gravitational pull on the surrounding matter. Since the dark matter is distributed in a less clustered manner than the luminous matter, the apparent average density seems to increase as larger and larger scales are probed. For a long time it was hoped probing sufficiently large scales would uncover a critical density of dark matter.

Today it seems unlikely that this hope will ever be realized. It is now possible to probe the average density of the Universe on scales large enough to compromise a fair sample of the Universe. We present the so-called "cluster baryon fraction" as one illustrative example of the strong evidence in favour of a Universe of subcritical density. Rich clusters of galaxies are the largest gravitationally bound systems in the Universe. Although rare, these systems are excellent laboratories for studying the composition of the matter filling the Universe.

Using nuclear physics one can determine the baryon density of the Universe. With the density of baryonic matter known, the total density can be determined from measuring the baryon fraction. The baryonic mass of a cluster can be determined by adding the masses of the constituent galaxies inferred from their light to the mass of the hot intracluster gas, which can be determined from X-ray observations of emission from the gas. The total mass can be determined by a variety of methods. The motions of the constituent galaxies allow one to determine the depth of the potential well and hence the total mass of the cluster. X-ray observations allow the same to be done with the gas, and gravitational lensing of background objects by the gravitational field of the cluster, resulting in the distortion in appearance of background galaxies, provides a completely independent check of the total mass.

These techniques, and a number of independent techniques as well, suggest a Universe with approximately one third of the critical density. Although a Universe of critical density cannot yet be ruled out definitively, the possibility of a critical Universe now appears like quite a long shot.

Click here to find out more about the consequences of the Universe of sub-critical density.